Mária Telkes, a solar energy pioneer. The Hungarian-American biophysicist and inventor Mária Telkes pioneered solar energy by inventing a solar oven, a solar desalination kit and, in the late 1940s, she helped design one of the first solar-heated houses.

Mária Telkes, born on December 12, 1900, in Budapest, Hungary, emerged as a solar energy pioneer long before the world would turn to renewable energy. She invented a solar oven, a solar desalination kit and, in the late 1940s, she helped design one of the first solar-heated houses. She is known as the Sun Queen.

Telkes, who came from a Jewish family that converted to Christianity, studied at the University of Budapest and then later in Switzerland at the University of Geneva where she mastered chemistry and physics, and earned a Ph.D. in 1924.

In 1925, while visiting her uncle in Cleveland, USA, she worked along the renowned surgeon George Washington Crile who performed the first successful blood transfusion.

Telkes dedicated the next 12 years of her life to researching the energy changes cells undergo during death or cancer, resulting in the publication of their findings in a collaborative book.

Upon becoming an American in 1937, Telkes joined Westinghouse Electric, where her focus shifted towards solar energy in 1939 upon becoming a member of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s (MIT) Solar Energy Conversion project.

As the world grappled with the Second World War, Telkes was enlisted by the Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD), which worked on the Manhattan Project. Her task was to leverage solar energy to transform salty water into drinkable water, addressing the critical issue of dehydration faced by soldiers at sea.

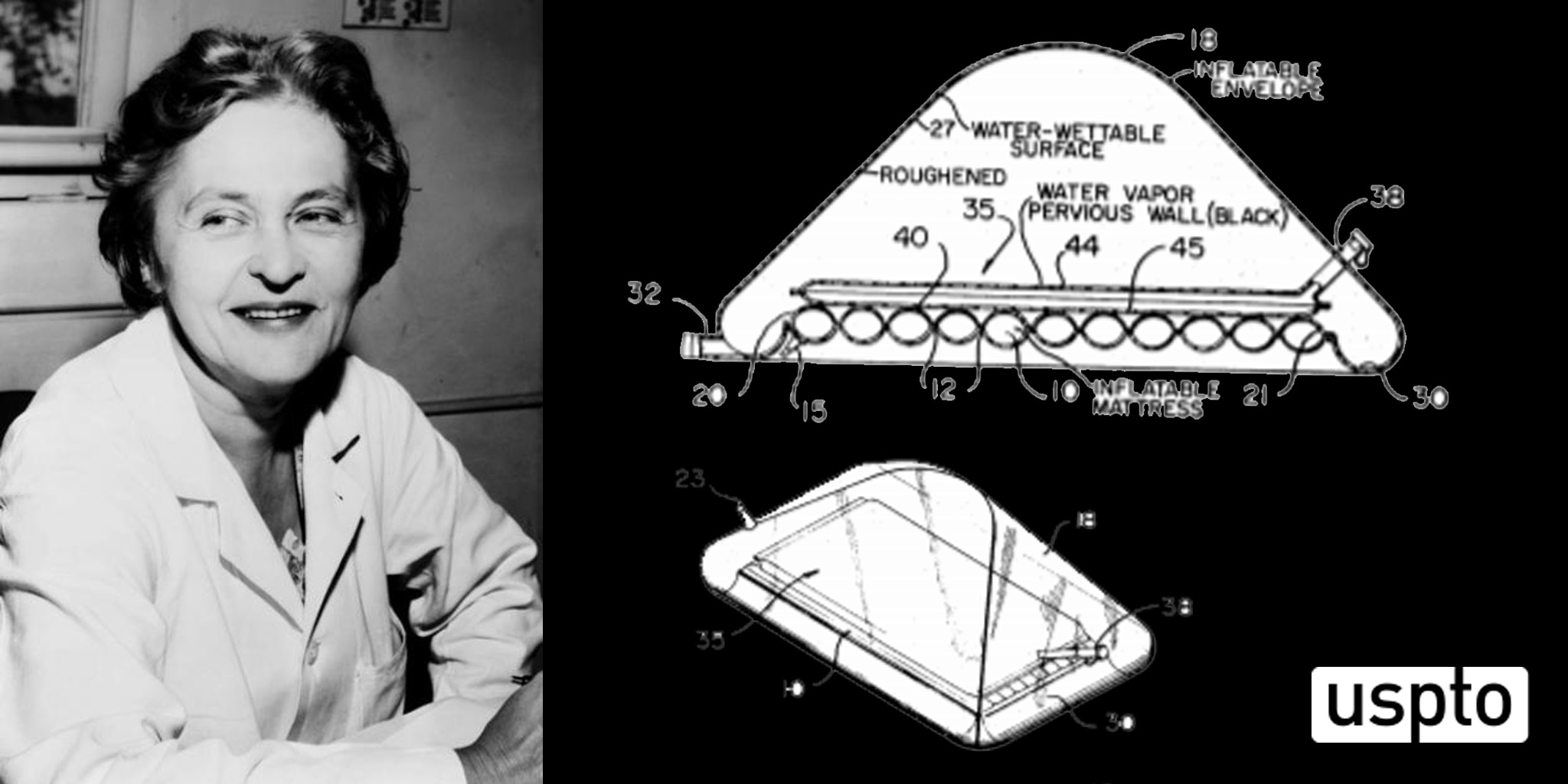

Maria Telkes solar energy invention so soldiers could drink water at sea

In response, Telkes invented the first solar water distillation device, capable of producing one liter of drinkable water per day using seawater. This innovation quickly became a standard component in every soldier’s pack, earning her a merit from OSRD for her invaluable contribution.

Maria Telkes dscribed the science of solar desalination in this paper from 1953

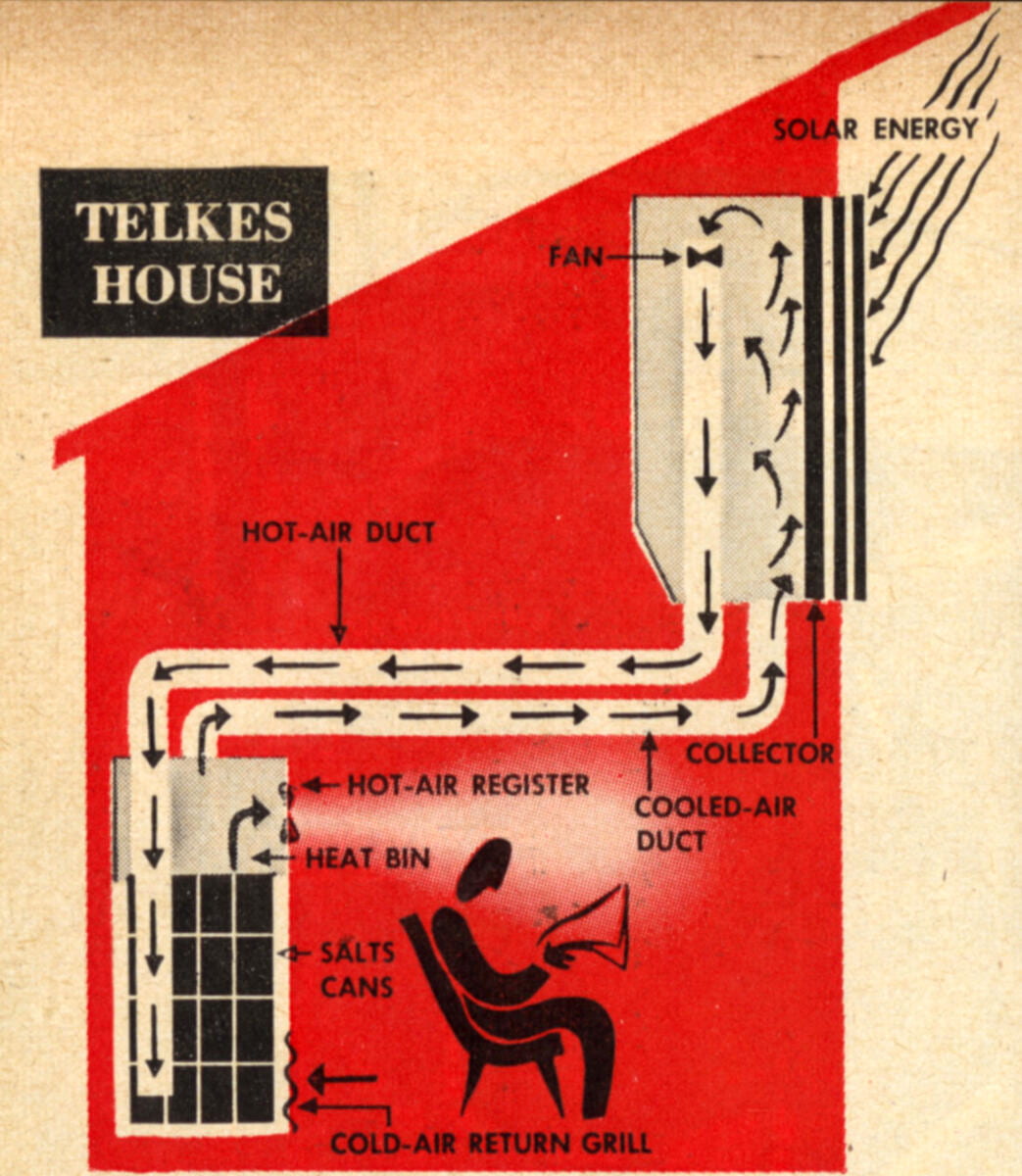

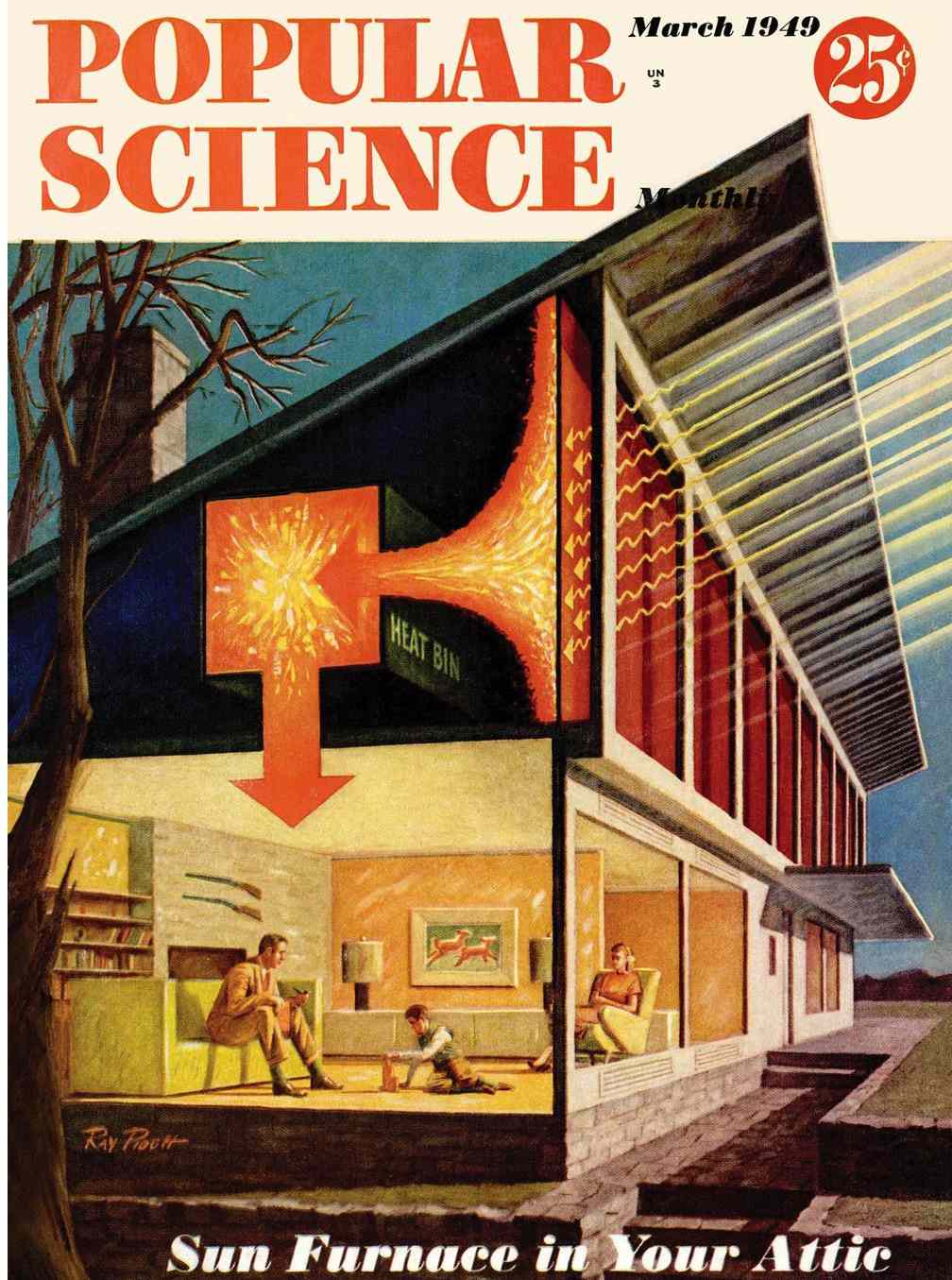

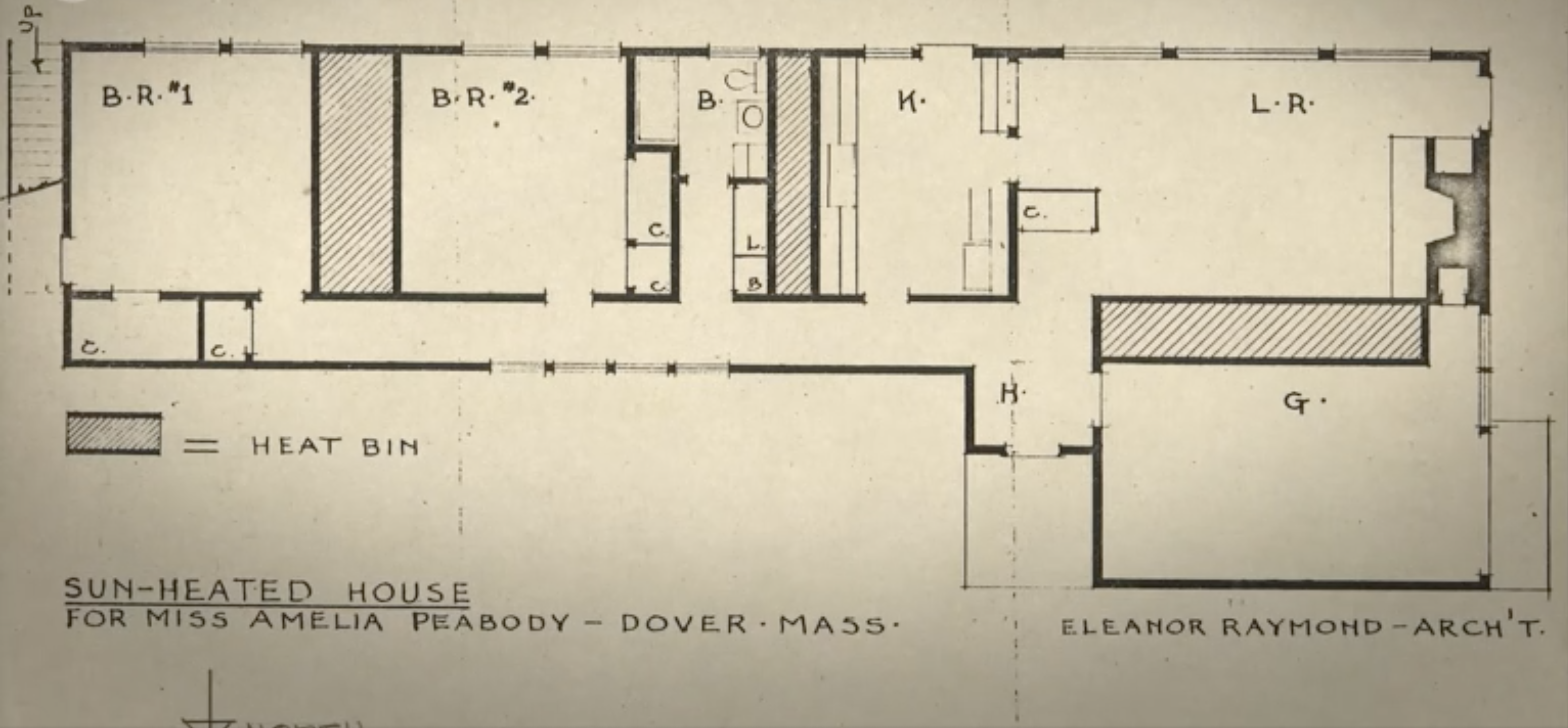

However, Telkes’ most renowned invention was the creation of the first solar house in 1948, the Dover Sun House, near Boston, designed by Eleanor Raymond and tested by the Némethy family, Telkes’ relatives.

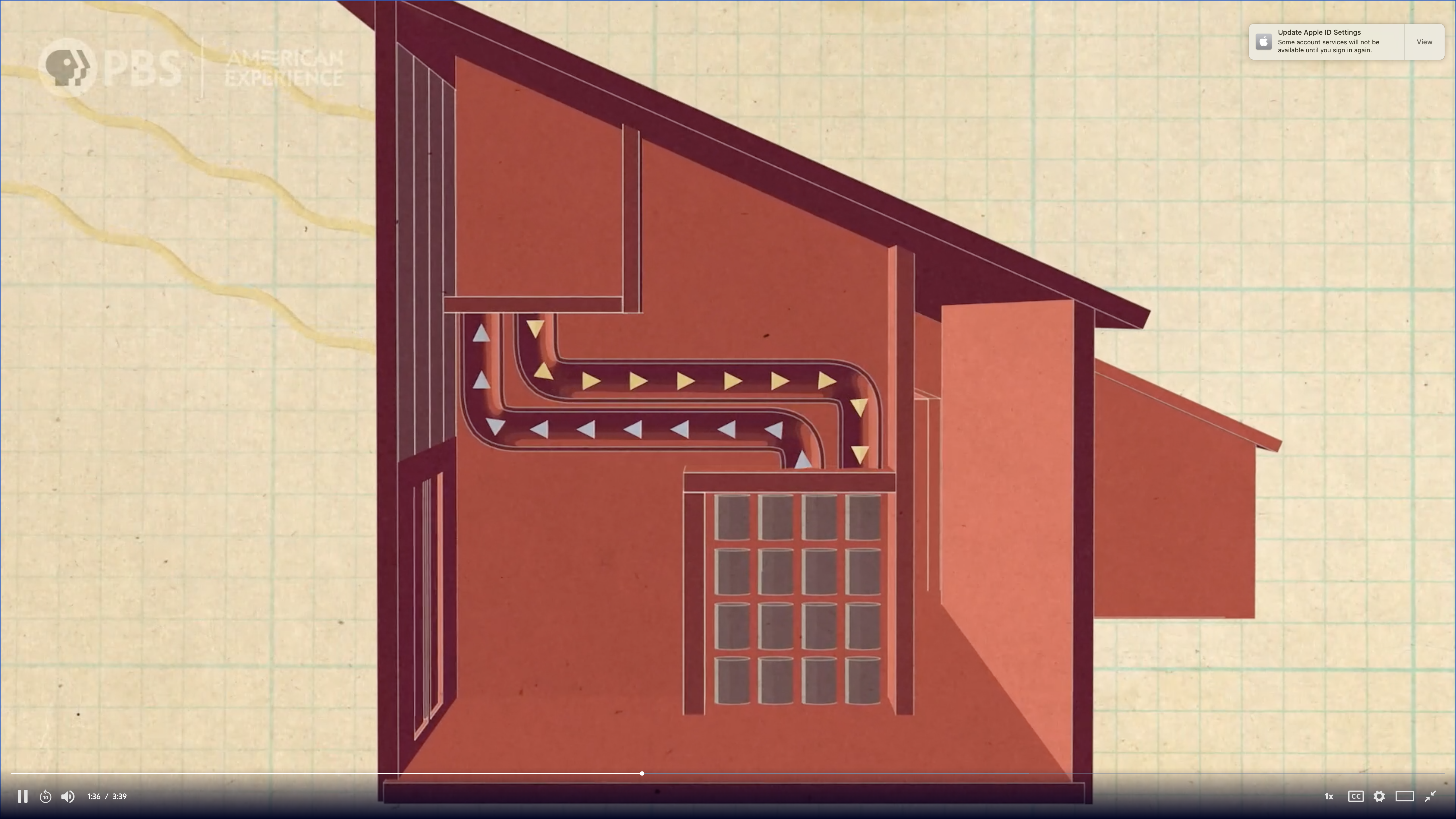

Maria Telkes and the Dover Sun House. The large windows faced the sun and collected heat and stored the energy in salts. Dover Sun House was one of the world’s first solar-heated houses. It was designed by architect Eleanor Raymond and had a heating system developed by physicist Mária Telkes. Client Amelia Peabody made it noteworthy for being “exclusively a feminine project.”

To tackle the challenge of storing solar energy for use on cloudy days, Telkes ingeniously employed a glauber salt solution (natrium sulfuricium) with a low melting point (32 °C) and high enthalpy of fusion, capable of storing solar energy for up to ten days.

Despite initial challenges – the unusually cold winter of 1948 and subsequent leakage in the solution tanks in 1953 – the solar house laid the groundwork for the acceptance of solar energy as a viable heating source.

“It was a proof of premise, a radical idea for her to be thinking that broadly and to think that far ahead and actually create a liveable house as an experiment,” says Andrew Nemethy, who was a boy who lived in the Dover Sun House growing up. “She needed astronauts, and I guess we were the lucky ones,” he said in a PBS documentary.

This marked a significant shift, considering that sustainable development was not yet a recognized term. People began incorporating solar panels into house designs, often complemented by traditional heating systems in areas with insufficient sunny days.

The Dover Sun House was demolished in 2010. A PBS documentary explores the contribution of Telkers and the Dover Sun House that would be heated only by the sun in a New England winter.

Maria Telkes outside the Dover Sun House in the PBS documentary about the Dover Sun House.

Telkes received the Society of Women Engineers Award in 1952, earning the moniker “The Sun Queen” in the United States.

In 1953, when Telkes was at New York University, she received a Ford Foundation grant to develop a solar stove that could be used in developing countries. Like the designs previous, she took a simple approach.

The stove was constructed as an insulated metal box equipped with doors on both ends, topped with glass over the food placement area. Harnessing the sun’s rays, the glass amplified their intensity, aided by four metal plates strategically angled at 60 degrees.

Diagram of Maria Telkes solar cooker

Triangular mirrors positioned between the plates further enhanced the amplification of solar wavelengths. Remarkably, the stove could reach temperatures of 400 degrees, requiring no specialized materials for its construction and boasting an affordable price tag of merely four dollars.

Dr. Maria Telkes, “world’s most famous woman inventor in solar energy,” speaks with Dr. J.E. Hobson (left) and Thomas K. Hitch.

Its user-friendly design (you can download the instructions here) found a welcoming market in midcentury India, precisely the tropical climate its inventor had envisioned. Telkes enthusiastically praised its merits to a reporter during a cooking demonstration, expressing, “Everything seems to taste so much better when it is cooked by the sun.”

In 1977, the American Solar Energy Society honored her with the Charles Greeley Abbot Award. At the age of 90 in 1990, Telkes submitted her last invention, leaving an indelible mark on the field.

Returning to her hometown, Budapest, after 70 years, Telkes passed away on December 2, 1995, at the age of 94. In recognition of her unparalleled contributions, she was posthumously inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 2012, alongside physicist Dénes Gábor.

Mária Telkes’ legacy endures as an inspiration for future innovators and a testament to the transformative power of solar energy in shaping a sustainable future.