Plastics are washing up everywhere. A Greek-Israeli architect explores the problem while on daily walks. And offers solutions and people driving innovation.

For the past three months we’ve been living on a Greek island, Aegina island, a marine-dependent community and economy. In my morning walks along the sea front, I meet neighbors, dog owners, couples, and joggers, who enjoy the outdoors in a climate-changed warm winter.

My walk passes by rocky and sandy beaches, and small docks with fishing boats. It also passes by sculptures by renowned artists Yiannis Moralis, and Christos Kapralos, the former residence of author of “Zorba the Greek”, Nikos Kazantzakis, overlooking the Saronic sea.

Elias Messinas collects plastics washed up from the Saronic Sea

I also pass by the Bouzas lighthouse, exquisite chapels like Aghia Filothei and Agioi Apostoloi, studios of artists, like Christos Kapralos and Nikos Nikolaou, and the former residences of archaeologists Gabriel Welter, and Belle Mazur, who studied and published the ancient mosaic of the local synagogue dating from the 4th century CE.

The morning walk is like a history tour. With such a legacy on the island, it is difficult to remain indifferent when encountering a plastic bag or a plastic bottle or a white piece of polystyrene foam stuck between the rocks or lying on the sand on the seashore. Especially near one of these important cultural heritage sites.

Living in a sea-dependent community, one realizes the practical meaning of the Cradle-to Cradle cycles. The technical cycle, such as the manmade environment, where waste must be carefully disposed and reused. The biological cycle, or the natural environment, where organic waste free of chemicals is absorbed back into the natural ecosystems. Biological cycles can also be generated by human activity, like composting household organic waste at home.

In reality, keeping the two cycles apart, seems like a Herculean feat, especially in communities who still struggle with basic household waste management. So, the system has flaws. Leading to waste entering the biological or natural cycle, in particular the marine environment, and in particular, through plastic waste pollution. It may prove to be a ticking bomb, as polluting marine life and habitats in the sea and seashore threatens the human food chain through the consumption of local fish.

This local community of 14,000, growing to 40,000 or more in the summer, is a small percentage of the global more-than 6.4 billion people who live in coastal communities in 192 countries. Collectively, they generate 99.5 million tons of plastic waste discarded within 50 km of the ocean. Although, 8.3 billion tons of plastics were produced in the past sixty years, only 9.5% were recycled. The numbers are certainly a reason to worry. With an estimated 150 million tons of plastic already polluting the world’s oceans, 9.1 million tons are added every year, with an estimated growth of 5% annually. Studies estimate that by 2025 plastics will be equal to one third of fish (by weight), and in 2050, plastic waste will weigh more than fish stock.

Plastics in the sea, decompose and break into tiny fragments, called microplastics, that threaten sea life. Plastic waste pollutes the beaches and is often riding the waves. But, can also sink in the seafloor, affecting marine organisms in their reproduction. Plastic waste may cause injuries and death of marine species. Studies show that plastic waste has affected at least 267 species worldwide. Further, the human food chain, and the local economy, are also affected, as coastal tourism is directly dependent on the quality and health of fish, sea and seashore.

As I observe plastic polystyrene pieces and fragments, plastic bottles, bottle cups, straws, lighters, ropes, hangers, wraps, bags, and wrappers, in my morning walks, I often try to imagine ways of dealing with this worrying issue. I would prioritize the reduction of plastic production and consumption. Some countries, like Canada, are already considering such moves, although the COVID pandemic caused a serious regression in phasing out single-use plastics in many countries.

The gold dust bought at Walmart may make your graduation photo pretty. But one blow and it’s forever cycling as microplastics that will get into our lungs.

Another solution would be to substitute plastics with bio-degradable materials. On the island some businesses already use bio-degradable bags. However, most businesses still opt for the cheap plastic choice. Education is key in raising awareness to prevent irresponsible disposal of plastics. Education can also encourage people to substitute single-use plastics and plastic products in their daily routine.

Local and national governments could tax the use of specific plastic products, considering the damage they cause at local marine ecosystems. I often think of the day when consumers’ IDs will be printed on the plastic product, container or wrapper, and consumers would be subject to fines. Finally, the day may come when plastics are banned, or replaced by bio-based alternatives.

These actions would certainly tackle the problem. However, they would take may years to realize and bring results. This is why many organizations choose immediate action.

For example, the Aikaterini Laskaridis Foundation in collaboration with the Netherlands based design firm The New Raw, have initiated the BlueCycle initiative to collect and reuse plastic waste from shipping and fishing activities. They create raw material to produce high quality 3D printed urban furniture and other design products. [Listen to ECOWEEK Green Talks podcast with architect Panos Sakkas of The New Raw]

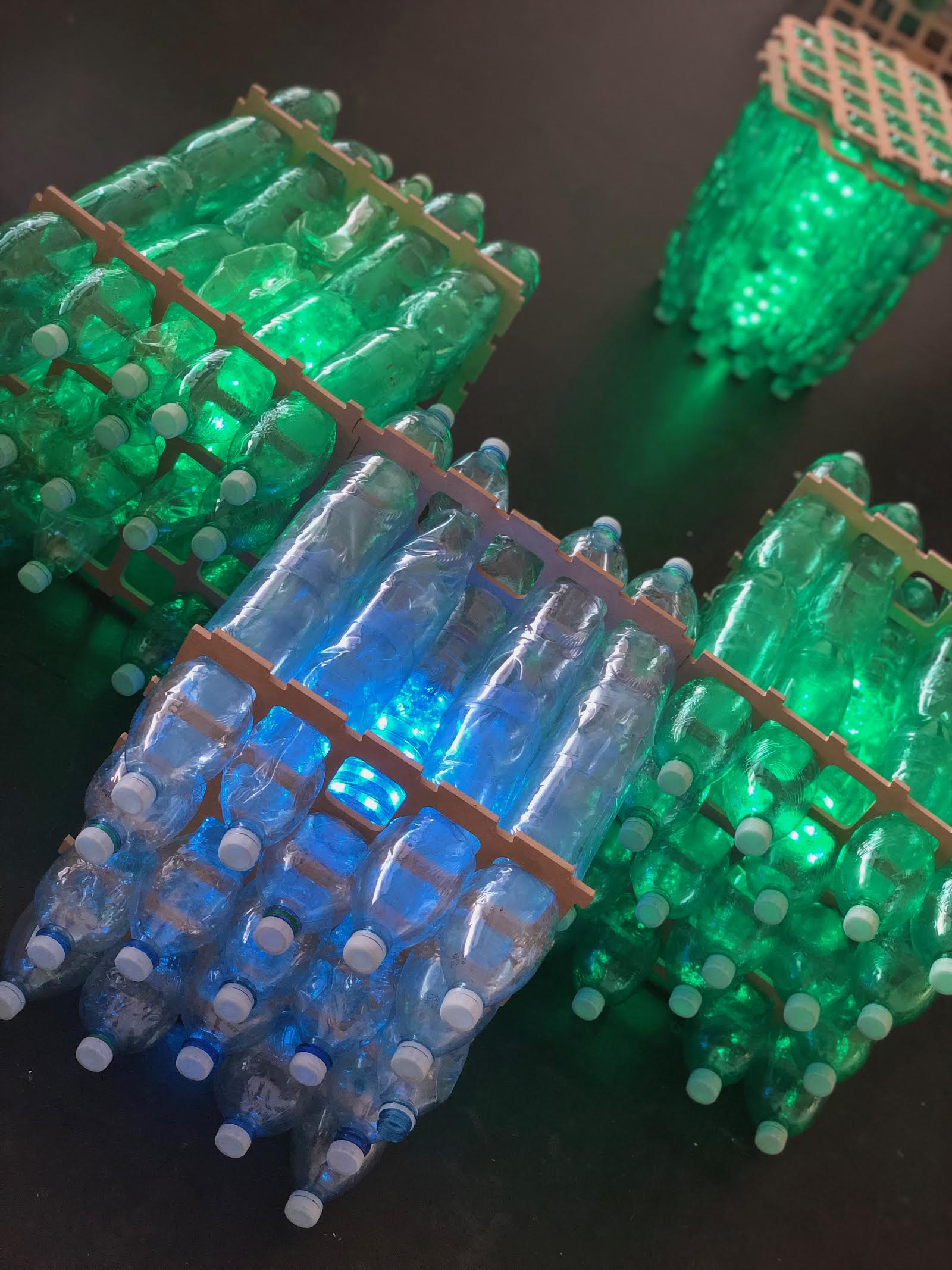

PetMat, a Prague based NGO that upcycles plastics

Prague-based NGO PETMAT focuses on the reuse of plastics, in the form of recycled PET in 3D printing of architectural projects, in creating the ‘PET(b)rick’ through recycled plastic blow molding, and through design pieces constructed of empty water bottles. [Listen to ECOWEEK Green Talks podcast with Katerina Novakova of PETMAT]

The New Raw recycled plastics from fishing

The Polish Recycling Band young musicians build and perform in instruments created in collaborative workshops, by using plastic containers that otherwise would be sent to a landfill, or pollute the sea.

At ECOWEEK workshops, we guided young architects and designers to engage in circular practices in design and reuse waste such as plastic bottles, furniture, ceramic pots, wood, and wooden decks and pallets. They used these materials to upgrade the school yard of a public elementary school in Crete, Greece and to construct a wooden outdoor exhibition space in an urban park in Milano, Italy.

ECOWEEK 2016 in Crete, Greece – Plastic bottes and reused materials upgrade a public school yard

There is also much to do on an individual level. For example, at the island, in my morning walks, when I see plastic waste by the sea, I stop and collect it. It has become part of my daily routine, a sort of meditation that does good both ways. It is also a great way to socialize. One morning, for example, I was joined by two young activists from Canada.

Cyrielle Noel and Georgina Faber are both active environmental advocates who engage in marine and coastal planning and design, research and consultation, and community engagement.

Through Eau daCité, their social enterprise, they reconnect cities, citizens, and companies to their original source of urbanization: waterways. Eau daCité promotes waterway literacy, activate sustainable development and connect social ecological transformation.

Inspired by this unexpected visit this Christmas, I invite readers to join me in Greece, or create your own group in your community, to remove plastics from the marine environment. It is truly fulfilling and empowering to know that you can intervene in reducing plastic pollution right now. To clean up natural ecosystems and reduce human exposure to plastic pollution. We can make our world a cleaner and better place.

—-

Elias Messinas

Elias Messinas a Yale-educated architect, urban planner and author, creator of ECOWEEK and Senior Lecturer at the Design Faculty of HIT, where he teaches sustainable design and coordinates the new SINCERE EU Horizon program, which aims to optimize the carbon footprint of cultural heritage buildings, through innovative, sustainable, and cost-effective restoration materials and practices, energy harvesting, ICT tools and socially innovative approaches. www.ecoama.com and www.ecoweek.org